I’m an ugly crier.

I don’t cry often, but when I do – it marks me for days. Puffy eyes, swollen face, flushed, and miserable looking. It’s not something I can hide. If I cry in therapy I feel like everyone notices me on the way out. Yeah, just going through some stuff. I normally exert a huge amount of strength to get somewhere private before letting loose, but it isn’t always possible. It’s a bad deal.

I’m a deep , griever. I always have been.

There is no way to measure emotional or physical pain. Because of this, it is impossible to know how we compare to others – do we grieve more? Less? Are we average? Pain isn’t like other ailments. When someone tells me they had a glucose level of 32, for instance, I can relate. I know how awful that is. I’m able to say – I’m so sorry. I know how awful that feels. Had I not experienced it myself, though, I could only try to empathize with their description of it. We can never truly know what another person is going through. We can only try to relate it to something in our own lives. Try to imagine how it would feel, if it were us.

This inability to be accurate causes difficulty when discussing emotional or physical pain. We might feel we don’t have the right to discuss our grief. We say things like “I know I have no right to complain” and “I know other people have it worse.” This self-invalidation is a pre-emptive strike. We fear others reminding us who had it worse. How much we have to be thankful for. That, unless we have suffered the very worse scenario, we can’t speak of it without also dismissing it in some way. Sometimes these internal conversations separate us from our greatest resources – the comfort of others.

The first time I remember experiencing a deep sense of grief was around 10 years old. My family had moved from Denver to Kansas City. I don’t remember having any bad feelings about the move ahead of time. I took it quite matter-of-factly. The grief came later, after the move, when I failed to thrive in my new environment. My youthful confidence was knocked out of me pretty quickly. I was not able make friends easily. As I would do many other times in my life, I turned on myself. Accepting that I was not a child anyone would want to be friends with anyway. I became silent, bound by my shyness. Eyes downcast, in the hope that if I couldn’t see you, you could also not see me. During lunch recess, I would climb to the top of the tallest playground equipment and strain my eyes towards the Denver mountains. I grieved for my life there, and for the younger me who was not so aware of my shortcomings.

I had times of being nearly paralyzed in my youth by things that didn’t seem to paralyze others. On one occasion I was able to fly by myself to Salt Lake City to see my grandmother. She was a person I always felt very close to. I’m the oldest of 8. To have my grandmother to myself was rare. She made every meal and snack special. We watched Anne of Green Gables in the evenings. Because I was not yet tempered in these things, I felt 100% of it. I counted the sleeps till the visit. I woke up excited for what we would do that day. I went to bed smiling. I’d given no thought to how it would feel when it was over. I was bereft. Consumed with the longing to have that time back. That was 40-something years ago. I can still recall the physical pain of this grief. It felt like a permanent part of me. I found myself unable to function or smile. This scenario repeated itself in different ways until I learned to protect myself from the after. To this day, I do not allow myself to get really excited about an event or trip. We can make plans to travel 6 months out. I will not even really take notice until a week ahead, when I am able to distract myself with preparations and guilt over leaving. I realize that by doing this, there is joy available to me that I outright refuse. Even with the logic of a grown woman, I still superstitiously believe that anticipation before and pain after are delivered in equal amounts. And thus, I have deemed anticipation dangerous to me.

I had one of those experiences in my early 20’s that people base their unwavering faith on. This was induced by the grief I was feeling over a long period of separation from the young man I loved. We had plans to be together when he returned, but this gave me no comfort as I had a period of several years to get through before this could take place. We’d said our goodbyes at the airport earlier that day. My grief was very dense at this time. And, because I had known this was coming, my grief and anxiety had been escalating for some time before. I was in my college bedroom. I’d gotten off my bed to go get more Kleenex (in the time since this event I’ve converted to washcloths – they are SO much more absorbent) when I had the sensation of being lifted into the air and cradled in the softest of blankets. A sudden peace came over me. I had a strong feeling of comfort, a knowledge that everything was going to be ok. The time felt short, suddenly and I had a knowledge that this would all be worth it, in the end. I’ve had others tell me that they have hoped and prayed for an experience like this. And that this is certainly proof of a higher power watching over us. I am never quite sure how to respond. Because, yes, this was a very unique, out of body experience. It was also entirely wrong. Wrong about him, wrong about us, wrong about time, wrong about any of it being worth it. The spot where I’d felt transfixed in space would later become the spot from which my sister would lead me, weeping and pale, having barely survived months of neither eating nor sleeping. It was not ok, at all. I’ve spoken of this room before. It is the place where I believe a ghost of me remains. Not because it was the spot of a conversion experience but because my later grief would emanate from me, staining the walls of the room permanently, from this same person.

I had the briefest of 3rd pregnancies. It lasted just six weeks – about the time a woman would just be finding out they were pregnant. Briefness aside, I was heartbroken. This child of my imagination had seemed so clear to me. I’d felt guided along the long road back to her. This was another, final case I attributed to the will of a greater power. It felt like this was a sure thing. I didn’t doubt it was going to happen. Only now, she was gone and this was my last stop on the pregnancy train. I’d known going into this there would be no more chances for me. And there weren’t. I felt terribly isolated at this time, for the mere fact that I had barely been pregnant. Only a few people in my life even knew this was happening. By any measure, this is the secret part of pregnancy. Where you don’t want to tell anyone yet – because something could happen. And it had. While I knew numerous women who had miscarried, my loss did not seem anywhere as valid. I felt I had no right to this grief and closed in on myself to feel it alone. I didn’t believe there was anything anyone could say that would be the right thing. It wasn’t meant to be. You can always have another baby. Well, something was probably wrong with it. None of the things usually said in these situations seemed right for my situation.

I have a friend who lost a baby at 24 weeks. It was a heartbreaking situation. A very valid loss. I would have never considered going to her for comfort, much less comparing our grief. The comfort, though, was given to me in abundance when she came to me and compared our grief. She said – I’ve lost a baby too. I’m so sorry. This act of compassion validated my grief. What I’d lost literally was a grouping of cells that touched down long enough for a positive blood test, then dissolved into nothingness. My figurative loss was much deeper, of course. It is a loss I validate each year when I go for my annual gynecological exam and write that I have been pregnant 3 times. It is the only way she is remembered. The emptiness of it does still hurt me, at times. In the space where she was supposed to go.

In previous entries I have mentioned a close friend of mine – the two of us had terrible 2019’s. Although our circumstances were quite a distance from each other, we were held in a positive trauma bond based on the severe depressive episodes we each found ourselves in. She’s a math person and she is the one who let me in on the ‘bouncing theory’ of grief and healing.

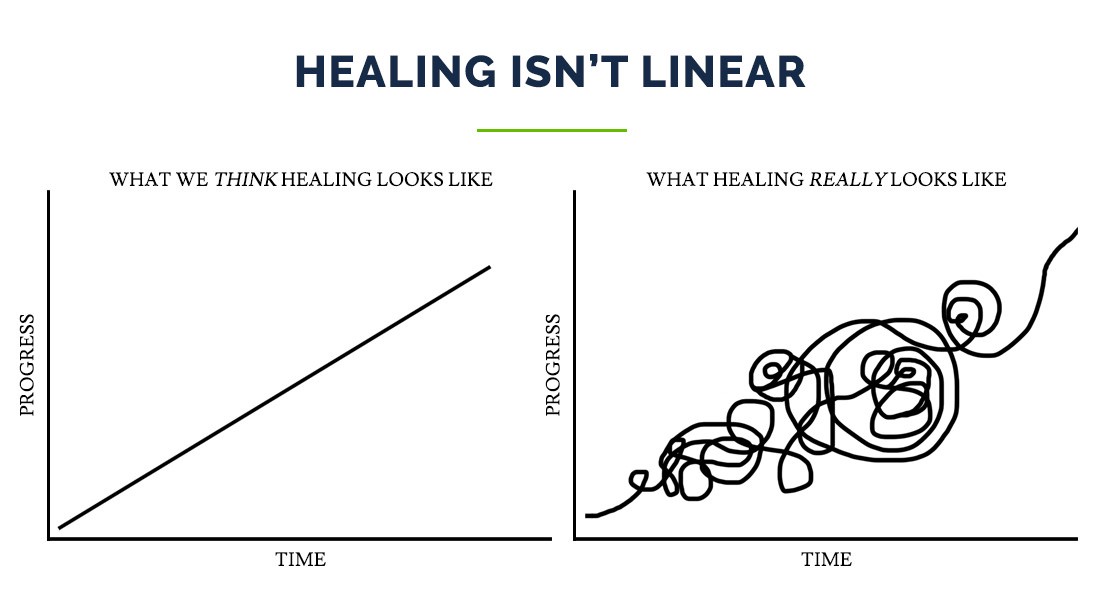

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if grief were linear? If we knew each day would be a shade lighter than the last. If this were the case there would be a mathematical equation for it. A way we could calculate the date it would end and peace would return to us. The ways grief is not linear is what makes it so difficult in the first place. We don’t know how long it will last. The day after we think we are getting better, we are pushed roughly back. This ongoing struggle to heal can very much make us believe it is never ending. Grief doesn’t give us the courtesy of being orderly.

Grief is more like a bouncing ball. Bouncing impossibly high at first, traveling a great distance before it bounces again. Shifting wildly within us. In time, it will lose some energy. The bounces won’t be so high, the jumps it makes won’t be so long. Perhaps it will never come to a complete rest, but it will continue along it’s transference of energy. My friend and I began referring to our bad days as “bounces.” Some would disappear by morning. Others seemed endless. It became an understanding between us. “I’m in a bounce.”

Emotional wounds are not unlike physical ones. Perhaps you have a knee that aches when the weather turns colder. Maybe an entire area where you had surgery is numb for years then starts to shoot pain along those nerve endings. You might be minding your own business doing your grocery shopping when the sharp blade of loss slips in between your ribs. The perfume that person you just passed was wearing. A song that takes you to an earlier time in your life. A situation that tears open a poorly healed wound from before. Or, as we evolve, we mourn old losses in new ways. The absence of a person that should be here to see what you are seeing. A cruelty done to us that we hadn’t realized as such until this very moment.

Healing is hard work and a long road. The bouncing ball of grief, at times, causes us to doubt that we will ever fully escape it. We hope to find a place of peace and understanding. A time when you will not know this pain. As quickly as the tide comes in, it can go back out again. We have a moment of peace or of believing we will get through this. I imagine this is what keeps us going. The hope that things will be a little easier tomorrow. That perhaps next year this time will only be a memory instead of something so poignantly felt.

Hope is a very human trait.

How to Support Your Healing Process (not my words, link to full article found at the bottom.)

1. Honor Your Pain. Avoidance of pain increases it. To heal, you must pass through the doorway of grief. Emotional wounds are beyond “sadness”; they’re felt in the depths of your being. Honor your pain; don’t run from it. Unplug, put time aside to reflect, and give yourself permission to grieve. If well-meaning people push you to “Get over it,” ignore them. Time and patience are key to recovery. Surround yourself with friends who understand that.

2. Reach Out. Being alone is part of healing, but long periods of isolation are unhealthy. Deep pain always brings out personal demons, such as blaming yourself, embracing victim-hood, or bitterness. Such choices breed entrapment, not freedom. Reach out to friends, find support groups or twelve-step programs, seek comfort in prayer, meditation, or philosophy —whatever brings you peace of mind. Instead of longing for a miracle, create one.

3. Take a Break. It’s important to take a break from your pain, and engage in healthy compartmentalization. Everyone finds relief in different ways. Some find it creative activities such as writing, reading, music, art, or movies. Others find it in movement such as dance, hiking, long walks, etc. Choose a task that allows you to escape by stepping into another reality, even if it’s only for a few moments. Don’t fret: Your pain will be waiting for you when you get back, but you’ll be better fortified, rested, and ready to face it.

4. Learn from It. I’ve heard it said that the road to wisdom is paved with suffering. Reflecting, exploring, and pondering, without self-attack or blame, opens you up to greater understanding and compassion for yourself and others. An attitude of learning will help you unearth value in the experience. You may also discover a curious new freedom: Recovering from an emotional trauma or heartbreak makes you stronger, wiser, and more resiliant.

5. Move On. Some people allow suffering to define them, shape them and, ultimately, rob of them of living. Many years ago, I was invited to attend a wedding between two widows in their 90’s. Every person who attended was deeply moved, not by the service, but by the spirit of the couple to keep living. After you give yourself time to grieve and mourn, after you reach out to others for support and make space for your recovery, you have to make a decision: Will you allow emotional pain hold you back or will you decide to use it to propel you in a new direction?