This is the third in a continuing series on the Robert E. Lee monument in Ft. Myers, FL. For Part 1 click here. For Part 2 click here.

Every monument has its story. The monument to Robert E. Lee in Ft. Myers, FL is no different. There are some 1,800 of these monuments in the United States. Schools, roads, and statues on public property memorializing the military leaders of a 4-year fracture of the United States. We gaze upon their likenesses, we remember their names instead of the 620,000 Americans whose lives were ended in the conflict.

It wasn’t always this way. In the years following the Civil War, memorials to the Confederate and Union dead were placed in cemeteries. I have seen them as such. A somber 58-foot granite obelisqe bearing the names of 1,640 Confederate soldiers that died while imprisoned in Alton, IL. The Lion of Atlanta, dedicated in 1894 to 3,000 unknown Civil War soldiers.

It’s not the same. Not to me. If this had been a case of a memorial to Civil War soldiers – either side – I would be making a very different case than I make here. I would fervently and, without apology, defend any monument to the military dead. Those who paid with their lives, whether I agreed with them or not.

This isn’t that. Robert E. Lee is not that. He lived a comfortable life after the Civil War. He had been pardoned by President Lincoln. He suffered no consequences. He moved to Lexington, VA with his family. He became the President of Washington College. He suffered a stroke. He perished two weeks later, having had time to make his final wishes known. Having had time to say his goodbye’s. None of the things afforded to the 620,000 Civil War dead.

According to the Southern Law Poverty Center (which maintains a national database) the vast majority of Confederate monuments were not placed in the wake of the war, as the dead were buried and mourned. They were placed between the years of 1900-1920, during the rise of Jim Crow (state and local laws that made way for decades of segregation) in the South. There is a second, smaller concentration of monuments in the 1960’s as the battle for Civil Rights was ongoing. (link here for more info)

The Ft. Myers monument to Robert E. Lee is unique in that its story spans both of these periods in American History.

Life wasn’t easy for the newly-freed slaves in the wake of the Civil War. While the 13th Amendment prohibited slavery in its more familiar form, the wording of such became immediately problematic in the former Confederacy.

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The former slaves found themselves able to walk away from the lives they had known but they had nowhere to live. No money with which to support themselves. No means of income save what they had already been doing. At the mercy of their former slavers hiring them to work. Paying them for their labor. These slavers had undergone no change of heart at the conclusion of the war. They still viewed the former slaves as their property. Lives they had paid good money for. Pay these people?

There was a way around this new landscape and it was discovered very quickly. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery – unless you happened to be a convict. You absolutely could press involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. And that’s exactly what happened. It’s now a crime to be unemployed. It’s now a crime to be homeless. Unlawful assembly and vagrancy are crimes. Who gets to make the determination of such? White law enforcement. White local government. The same people making the laws in the first place.

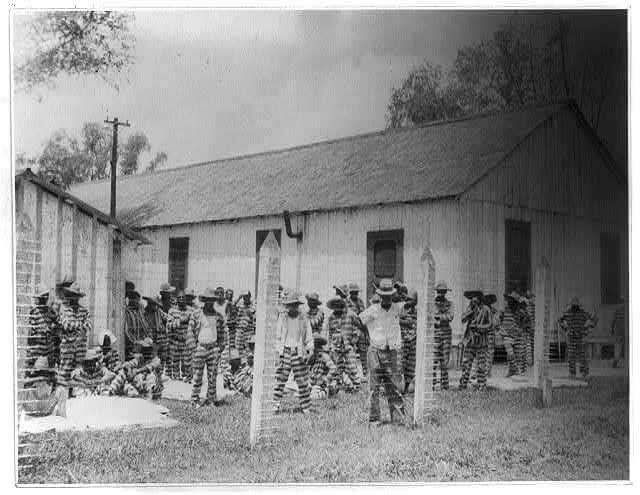

The former slaves found themselves back on the plantations, back doing slave labor. The only difference is now they wore a prison uniform. Overseers quickly became jailers. Sentencing for these crimes was harsh. Penal labor quickly became American’s new slavery. The former Confederate States began to incarceration for profit. Convict leasing.

The state of Florida participated alongside the rest of them. In fact, Florida was one of the first states to start this practice, within 5 years of the war ending. Florida leased its convict labor force harvesting timber and building railroads. Seeing a black man wearing a prison uniform became so common it was a bygone conclusion. The internal bias that a black man is more likely to be a criminal than a white man, that a black man is inherently more dangerous than a white man is a damaging bias that follows us even now, in our present day. It is undeniable.

Fort Myers was different. For a time. Fort Myers had remained rather isolated by its location. A sleepy, slow-growing city on the Gulf of Mexico. A winter destination, an escape from the harsher climates of the north. The easiest way to reach it was by sea. It gained transplants from the former Union states. Americans who were more likely to see the descendants of slaves as deserving of the American dream. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Thomas Edison, the most famous resident Fort Myers would ever have, arrived in 1885 to begin his 25 winters in his lovely waterfront home. He was searching for an alternative to rubber. He had extensive grounds, full of plants he hoped would aid in his endeavor. He explored different botanical filaments for his electric lights. Henry Ford joined him here in 1914, building his winter home on an adjacent lot to Edison. The influence of these two men helped shape Fort Myers into what it is today. The spirit of the city is a respite from the cold winters of the north. Money is plentiful. The coast is full of multi-million dollar homes. People flock here for the climate, it’s thriving downtown district, it’s historic architecture and it’s art.

(Thomas Edison (left) John Burroughs and Henry Ford (right) Ft. Myers, FL 1914)

At the turn of the century, though, Ft. Myers was still remote enough to escape some of the post-war influence we saw in other areas. An interdependence had formed in Ft. Myers, one where race did not hold the weight it did elsewhere. More than a third of African-American families in Ft. Myers owned their homes this time. 20% were working their own farms. Black men were known business owners and traders. Lee County had the lowest rate of illiteracy in the state amongst black males (8% against the states 26%) In the absence of official segregation, black and white families lived alongside each other. The local paper, the Ft. Myers Press reported the accomplishments of all citizens, often without any reference to color.

One of Ft. Myers most notable African Americans was a freed slave named Nelson Tillis, who had lived in Key West during the Civil War. Mr. Tillis went on to become more successful than many of his white counterparts. A white military officer officiated his wedding. He and his wife went on to have 11 children. His homestead grew to 160 acres, which he primarily farmed. His sons eventually moved to the banks of the Caloosahatchee River, living adjacent Thomas Edison. Mr. Tillis and his family lived, by all accounts, a prosperous life.

This was all about to change, rapidly, in 1904, when the railroad reached Ft. Myers. This new means of transportation brought two things with it. The first was an influx of white migrants from the Confederate states, attracted to the area’s reputation as a cattle hub and the plentiful hunting. These migrants held a lower, much more racist view of African-Americans than the more elite transplants from the North that had made Ft. Myers an earlier home.

The second thing the railroad brought was a new labor force that was predominantly black. The black population in Ft. Myers grew exponentially between the years of 1900-1910. That, along with the Confederate migrants, polarized the racial landscape of the city. The Fort Myers Press ran the following editorial piece as the rail line crept it’s way steadily southward.

It should be remembered that great changes are to take place in Ft. Myers in the next 12 months. In a month or two large bodies of colored men will be brought here to work on the railroad. It will require vigilant officers to preserve order in the new conditions. It will require a firm mayor and an equally firm marshal to handle the rough element that is sure to follow in the wake of the railroad.

Ft. Myers Press, June 25, 1903

It had already been decided, before the labor force even arrived, that things were going to change. A sterner hand, a more watchful eye, a more vigilant form of law enforcement. The attitudes towards the existing African Americans in Ft. Myers shifted with it. One of guilt by association.

Over the following decade, these long-standing black families would be pressured and prodded into a depressed area known as “Safety Hill” where both the quality of housing and roadwork were poor and undeveloped compared to the rest of Ft. Myers. This area was located just across the new railroad line. On the far side of it. Within a short period of time, the black citizens of Ft. Myers would find themselves, quite literally, on the wrong side of the tracks.

City directories track the movement of these residents. One by one, family by family, becoming the residents of “Safety Hill”. Remember Nelson Tillis, the freed slave who went on to own 160 acres and enjoyed the prosperity of his labors? His two oldest sons, Eli and Marion, who had worked the homestead with their father and lived adjacent to Thomas Edison are noted in the city directory as changing their residence to the segregated and harshly policed Safety Hill area during the time before 1920. These records show the degradation of even the long-standing black citizens in Ft. Myers.

(It is noteworthy that the area formerly known as “Safety Hill” area still exists, is still underdeveloped, and to this day, still contains the majority of the black population in Ft. Myers.)

It is against this rapidly changing backdrop that The Laetitia Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was formed (1913) and began collecting funds to install a memorial to a Confederate general who had never set foot in Ft. Myers.

Please join me in the coming weeks for more on this subject.

Sources:

Harrison, J. (2015). The Rise of Jim Crow in Fort Myers, 1885-1930. The Florida Historical Quarterly, 94(1), 40-67. Retrieved December 2, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24769253

https://www.history.com/news/13th-amendment-slavery-loophole-jim-crow-prisons