This is the fifth and final article in a continuing series on the Robert E. Lee monument located in Ft. Myers, FL. For part 1 click here. For part 2 click here. For part 3 click here. For part 4 click here.

Abraham Lincoln lived for only 6 days after the Civil War ended. Have you ever wondered how those few short days felt for him? Have you wondered if he was able to even pay attention at all to Our American Cousin in Fords Theater that night? In a story we are all too familiar with, his assassin, John Wilkes Booth, first jammed the door to the Presidential box then fired a fatal shot into the President’s head. He then lept to the stage, breaking a bone in his leg in the process and shouting “Sic semper tyrannis!” (Thus always to tyrants)

The Civil War did a number on President Lincoln. He wanted nothing more than for the Union to be restored. His predecessor, Andrew Johnson, at first committed to prosecuting the Generals of the Confederacy. Without exception, they had first been leaders of the United States military. They were educated, elevated through the ranks before they became members of the insurrection. Thirty-nine of them were indicted for treason. President Johnson found himself faced with two choices, though. On one hand he could prosecute, even execute these men and show the nation the consequences of taking up arms against your own country. On the other hand, he could choose to diffuse the tension between north and south and move towards unification. In the end, the betterment of the country won. The battered and war-torn United States began its tedious journey through reconstruction.

Fort Myers was a little late to the party.

In 1954 the United States Supreme Court made a landmark ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education. This decision abolished the practice of school segregation. Prior to this point, black students were educated in separate buildings than their white counterparts. The old laws had been put into place using the assumption of “separate but equal” policies, that all schools were alike aside from the students that attended them. This was far from the truth, however. Outdated textbooks, used uniforms and long bus rides kept minority students at a disadvantage for decades and dissatisfaction began to escalate.

Dunbar High School, in the segregated area of Ft. Myers, had become a beacon of community involvement and a vibrant part of the small black area of the city. The students there, though, were being subjected to the same injustices found through the segregated south. As the only High School black students could attend, black children as far as Naples (one hour) were bussed to Ft. Myers daily. The school had been built using handed-down plans. It received the discarded textbooks of Ft. Myers High School and the Dunbar area in general often found themselves having to raise up to 50% of the improvements to their schools instead of receiving monies from the city or county.

The ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education gave black students the hope that this situation would be remedied all through the south and the first black students began being escorted (at times by the National Guard) into historically white-only schools to an enormous backlash in their mostly white communities.

Despite these small advances, the wheels of justice were slow to turn. Across the south, counties, cities and school districts began to drag their feet. This necessitated a mandate, referred to as Brown vs. Board of Education 2, which ordered all segregated school districts to integrate “with deliberate speed.” The year was 1955 and the Lee County School District was requested to end the “biracial school system. ” They refused to comply.

Probe NAACP – Letter to the Ft. Myers News-Press

“First let me state that I am a ‘Yamdankee’ and not biased in favor of the Negro, despite the appellation. I firmly believe the Negro has his place, but it is with his own people. I also believe as did Lincoln that the Negro should never have social status with the white and not permitted to govern.”

Ft. Myers News-Press, April 9th, 1960

Nine more years would pass in Ft. Myers without any sign of school integration. It is now 1964 and a black student by the name of Rosalind Blalock applies to the all-white Fort Myers High School. Rosalind, a promising young lady, was planning a career in medical technology and applied for a transfer to the all-white high school in order to gain access to better science equipment and new textbooks. She was denied on basis of her race.

In response to this decision, Rosalind’s father brought a lawsuit against the Lee County School District and was joined by 20 other students of Dunbar High School. The NAACP picked the case up, boosting the attention on it. The NAACP complaint read, in part, “Many Negro students … who reside nearer to schools limited to white students are required to attend schools limited to Negro students which are far removed from the place and cities of their residences. Attendance at the various public schools of Lee County is determined solely upon the basis of race and color.”

Blalock vs. Lee County School District is ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and Lee County School District responds with a plan to begin desegregation the following year. With the 1st grade. This will be the class to be fully integrated, pushing the completion of desegregation well into the later 1970’s when this 1st grade class is scheduled to graduate

Ft. Myers wasn’t the only city having a difficult time with the Civil Rights Movement. It was happening all over the south. After decades of legal segregation, a wave of resistance was building. The strain of it was felt all over as the push for equality rolled forth.

The preceding year had seen the March on Washington and Martin Luther King, Jr. famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The year of Blalock vs. Lee County Schools, President Kennedy introduced the Equal Rights Act, which made discrimination illegal in public places based on a person’s race, color, religion or national origin.

Tensions were at an all-time high in America when Kennedy was assassinated. Kennedy’s predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, would sign the Equal Rights Act into law. Across the south, Civil Rights leaders were being lynched and shot. Emmet Till, Medgar Evans and Birmingham Church bombing had only recently happened in the south. People, black and white, were standing for racial equality and were being gunned down, sprayed down with fire hoses, beaten by police officers, and found hanging in trees. Black churches were being burned to the ground during this time in American history. Nobody had the luxury of escaping the growing pains that the nation was enduring. Pressure on the south to cease segregation increases and the reports of all these incidents catch the attention of the greater part of the nation. In the state of Florida at this time, only 2.9% of schools have desegregated in the 10 years since Brown vs. Board of Education was passed.

There is, again, a push to erect monuments to the Confederacy. The first push for these was seen during the Jim Crow Era when the laws of segregation were taking hold. This second flurry of interest in Confederate Monumbents seems in direct response to the Civil Rights Movement. For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. For every advance in the black community there is an equal and opposite “whitelash” in response. We see these monuments placed in and around courthouses, on public property, as the wheels of social justice within these buildings groan and wail. The Confederate Battle Flag sees a ressurgence in it’s usage, being added to the state flag of Georgia in 1957. The Klu Klux Klan regroups after the lull of segregation being firmly held in place by fear of violence and bloodshed. Local chapters of the KKK all over the south set forth to resist social change and halt the efforts of black people to improve their lives. In certain areas the Klan members work in the mining and steel industries and have access to the materials to make bombs. Birmingham briefly becomes known as “Bombingham” due to the sheer numbers of black homes that are destroyed.

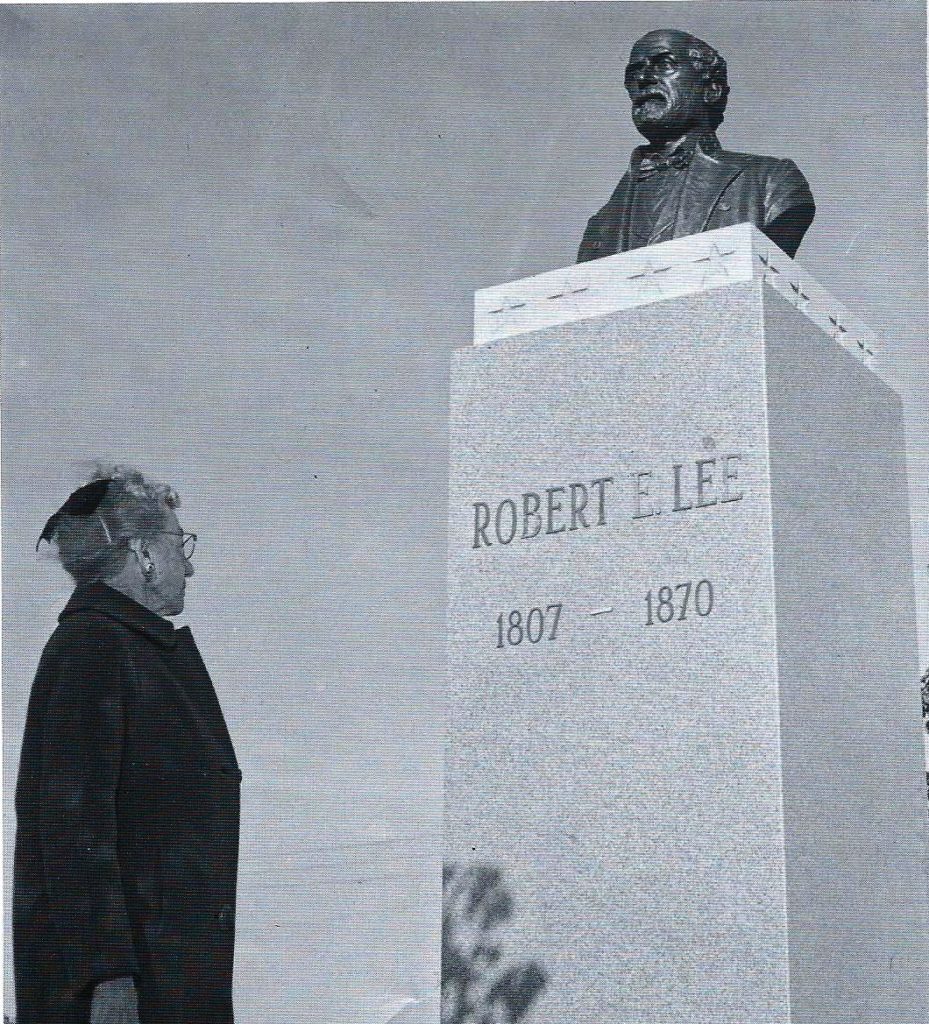

The Robert E. Lee Monument in Ft. Myers is unique in it’s timing as it spans both the Jim Crow and the Civil Rights surges of Confederate monuments. The Daughters of the Confederacy began their fundraising in 1913 but continued to be distracted by more noble causes. Between 1940 and 1953, there is no mention of the bust at all. Then suddenly, it again becomes the focus. It is of no other particular timing. It isn’t a significant anniversary of the war. It isn’t even a significant anniversary of General Lee. And yet, during this time of particularly heightened racial tension, it appears.

“General Robert E. Lee Statue To Be Put On Monroe Street.”

A $6000 monument to Gen. Robert E. Lee, for whom this county is named, will be erected on Monroe Street, within six to eight months Mrs. B.P. Roberts, chairman of the project for the United Daughters of the Confederacy said yesterday. … Members of the U.D.C working with Mrs. Roberts, have cleared the way to start the project. Approval of Mayor Paul J. Myers and cooperation of the Southwest Florida Historical Society, the Ft. Myers Planning Board and the city beautification committee was gained. The Lee County Board of Commerce will mail letters to business firms, clubs, and residents this fall, requesting contributions.

Ft. Myers News-Press, July 1st, 1964

September 25, 1965 the residents of Ft. Myers awoke up to the news that Lee Memorial Hospital will voluntarily comply with the Civil Rights Act. While this sounds noble, they had little choice in the matter. Non-compliance to the act was going to cost the hospital it’s federal funding. Beginning September 1, 1965, the hospital was going to be charged $8000 per month in violation. It is but one more defeat for the “this is the way it’s always been done” crowd.

For a time, the completed bust of Robert E. Lee sits in the courthouse with a collection box for contributions towards its base. Nickles, dimes and quarters are thrown in by the residents of Ft. Myers. Occasionally a $100 bill is thrown in. Hundreds of businesses and citizens donate to the memorial in the mid 1960’s. The civic groups that donate to the memorial receive write-ups in the paper and a roster of these people is permanently placed in the lobby of the Lee County Courthouse.

James William Clifford, a member of the Civil War Commission and Civil War memorabilia collector donates relics to the project. They are:

- A bayonet scabbard from the Yankee Line at Harper’s Ferry, WV.

- A 58 caliber mini bullet from the Rebel Line at the 2nd Battle of Manassas.

- A 58 caliber round lead ball from the Union Line at Gettysburg, PA.

- A 58 caliber mini bullet from the Confederate Pattern at Hamilton’s Crossing in Fredericksburg, VA.

- A brass sword guard from a Confederate campsite at Centerville, VA.

- A 12-pound shell fragment from the Yankee Line and a rusty Yankee bayonette and shenkle shell received years after the battle at “Bloody Angle” near Spotsylvania VA.

- A gun strap from Malver Hill, VA

- A Confederate belt buckle from Rebel Line at Wilderness Battlefield in VA.

A small group gathered for the unveiling of the monument.

This country encompasses a rich, warm, interesting land. It’s history is of self-reliant, generous, religious, warm-hearted, happy people. We hope and pray this country’s gay and happy past, amid her sunny beaches, waving ponds, blue waters, broad prairies and tall whispering pines, is in fact a prophesy for her future.

Ft. Myers News-Press January 20, 1966

The accuracy of the above statement depends, of course, on which side of the railroad track you happened to find yourself in 1966.

Fourteen years pass since Brown vs. Board of Education, five years since Blalock vs. Lee County School District, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr has recently been assassinated. Leaders of the black community in Dunbar volunteer to ride with the Ft. Myers Police Department in the wake of Dr. Kings assassination to curtail violence and rioting and keep racial tensions down. Their efforts are largely successful.

At long last, in 1969 the city is finally ready to get serious about school desegregation. Adding insult to injury, the city closes Dunbar High School and begins to bus Dunbar students to other schools. Some of these students will find themselves changing schools yearly as the population of Ft. Myers shifts. In protest of having their beloved school eliminated, thestudents of Dunbar High School march across the Edison Bridge. Following in the footsteps of most racial justice decisions in Ft. Myers, their complaints go noted but largely unrecognized.

It will be 1999 before Lee County School District was declared equitable. A full 30 years will pass after Dunbar High School was closed and integration started in earnest before Ft Myers will fulfill their school desegregation directive. 35 years had passed before Blalock vs. Lee County School System is considered a closed matter.

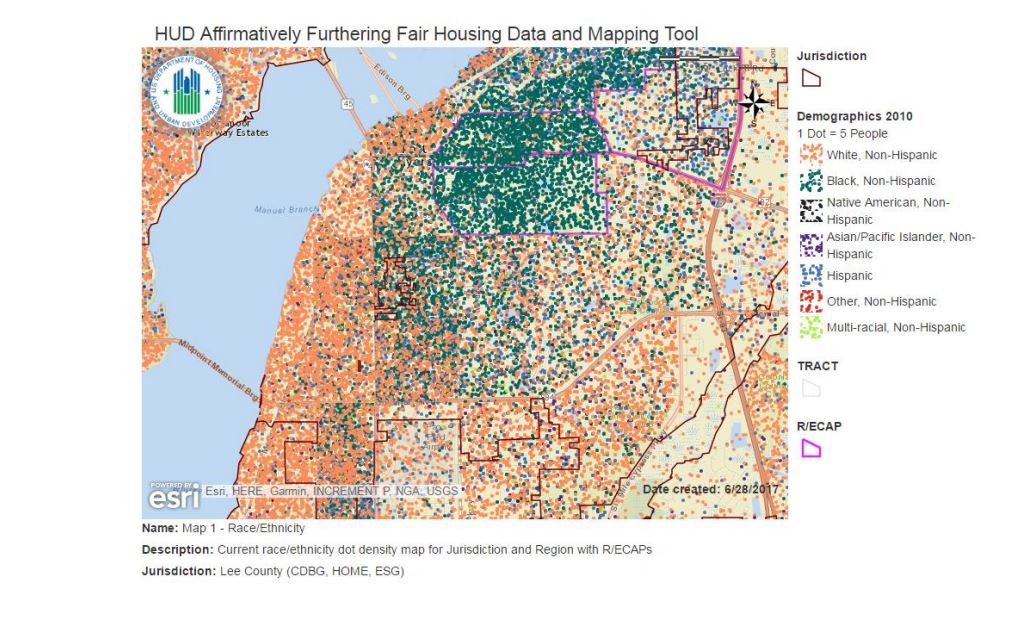

What happened to Dunbar? Well – when people were able to move from the area as segregation lifted, those who could did. Due to this population shift, Dunbar businesses found themselves in decline. While the former residents of Dunbar were no longer barred by law to live in other parts of Ft. Myers, they also hadn’t had the luxury of generational wealth and home ownership that white areas had during the same time period. The area to the west of Dunbar had escalated rapidly in property value during the segregation years. It wasn’t possible to make the jump. Bordered by the Caloosahatchee River on the north, an industrial district to the south and the Interstate to the east, the Dunbar community is almost the textbook example of redlining. Dunbar remains, in ways, just as segregated as it was in the 1940’s, only without the benefit of its heart. As always, in the face of adversity, Dunbar continues on.

General Lee sat, gazing coldly towards the Ft. Myers Courthouse, largely overlooked until just recently. The racial tensions of 2020, sparked by the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, brought the General an uneasy focus. The bust of the monument was removed and taken into safekeeping by the Sons of the Confederacy. The base of the monument has sat, unadorned, since that time.

In October, 2020, the Ft. Myers City Council voted to remove the General Lee monument and place it in a museum. Thus far no museum has taken the city up on their offer, though. The point seems moot anyway as the Sons of the Confederacy have decided to retain the Generals bust, refusing to return it to the city although it has been deemed city property. The monument, 50 years in the making and seated in the most tenuous racial period of the United States has become King Solomons baby, cut in half in order to determine who cares for it most. Without both pieces of the monument of course, the priceless artifacts in its base will never be on public display and the monument’s full story will remain untold.

General Robert E. Lee – a man who never set foot in Ft. Myers or the county that bears his name. A man who was too busy to notice the Battle of Ft. Myers. A man who lived the remainder of his life in the comfort that 618,222 Civil War soldiers were not afforded. A man who only reluctantly took up arms against the United States in order to defend his home state of Virginia. A man who found himself surrendering all Confederate hope to Ulyssis S. Grant. General Lee, the man who died with the comfort of family after a long and full life sits somewhere in the city of Ft. Myers, hidden from protestors, hidden from the city, no longer casting his frozen gaze upon the endless traffic looking for parking on First Street. Revered by only a precious few.

The fates of the highest-ranking Generals of the Confederacy

- Samuel Cooper‘s final act was to preserve the official records of the Confederate Army and turn them over intact to the United States Government. He returned to his land in the state of Virginia where he spent his remaining years farming. He died at home at age 78.

- Albert Sidney Johnson was the only Confederate General to die in the Civil War. He took a bullet to the back of the knee at the Battle of Shiloh and his boot filled immediately with blood. He was helped to the sidelines where he lost consciousness quickly. A doctor was called to the scene but arrived too late. Ironically, a tourniquet was later found in General Johnsons jacket pocket. He was 59 at the time of his death.

- Robert E. Lee had resigned his post to Jefferson Davis following his defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg. The General reportedly rode out to meet his retreating army following the battle proclaiming “All this has been my fault.” The third highest-ranking Confederate General, Lee would become synonymous with the end of the war, surrendering the Confederate Army to Ulysses S. Grant following their defeat at the Battle of Appomatox. Lee would go on to serve as the president of Washington College until his death at age 62 from complications of a stroke.

- Joseph E Johnson went on to become a Democrat in the House of Representatives. His memoirs, when written, were highly critical of Jefferson Davis and became a fierce defender of Union General Sherman, to whom he had surrendered his troops. General Johnson even attended General Shermans funeral, refusing to wear his hat in the rain as a sign of respect. Joseph Johnson would catch pneumonia that day and die 10 days later at the age of 84.

- Pierre GT Beauregard, who would lead the attack on Ft. Sumpter and thus begin the Civil War, became a railroad executive and advocated for black rights. He died of natural causes at age 74 in New Orleans.

Four million people were enslaved in America at the time of the Civil War.

40,000 black soldiers fought and perished in the conflict.

200,000 African Americans were incarcerated and forced into involuntary servitude after the Civil War ended.

4,743 Americans were lynched during the years of 1882-1968.

A white male born today has a 1 in 20 chance of being sentenced to life in prison. For a black male, those chances are 1 in 5.