This is the second in a continuing series on the Robert E. Lee monument located in Ft. Myers, FL. For Part 1 click here.

It is an unlikely place, in my opinion, to find a monument to Robert E. Lee. Situated on the land of a former fort which, in turn, is located in (Robert E.) Lee County. While it sounds legit, the monument is a “Turducken” of inharmonious politics.

There are a few stories to be told here. The first is a short one. Robert E. Lee has no direct relation to Ft. Myers. General Lee never visited, never surveyed, never even traveled through here on his way to somewhere else. There was no city called Ft. Myers before the Civil War. Even during the war, there was no city. There was an abandoned fort from the Third Seminole War in disarray. Nothing more. That this fort fell into Union hands during the Civil War is even more reason General Lee would have never traveled here.

The second story is only slightly longer. How did Ft. Myers come to be located in (Robert E.) Lee County? This took place in 1887. Ft. Myers found itself part of Monroe County, the county seat of which was in Key West. Doing business with the county seat meant a week-long roundtrip journey. Ft. Myers was home to 1,500 residents at that time. Large enough to have a lovely High School; which happened to catch fire and burn to the ground. A delegation was dispatched to Key West to petition funds to re-build. The delegation was told that “if they were so careless as to permit a splendid $1000 building to be destroyed by fire they didn’t deserve consideration.” This didn’t sit well with the delegation (or anyone else for that matter) and a decision was made to break away from Monroe County. At the time, many of the residents of Ft. Myers were Confederate Veterans who still felt loyalty and devotion to General Lee. It was an act of rebellion and secession, what they were doing. It seemed appropriate, under the circumstances, to name the new county “in honor of the South’s noblest son” Lee County, FL was born.

The third story is the longest (but also the most interesting!) and this is the story of Ft. Myers and the Civil War.

The year was 1861 and Florida had just seceded from the Union. It was the 3rd state to do so. Florida was very important to the Confederacy. The state, being a peninsula, was easier to secure than those states that were landlocked. Florida was known as the Supplier to the Confederacy. Food for the troops. Easily able to reach the Eastern border of the Confederacy via the Atlantic Ocean and also the southern states in the Gulf of Mexico. Thereby supplying beef, pork, fish, fruit, salt, and molasses to an army of close to 1 million. A vital part of the Confederate strategy was to keep the inland roads and rivers of Florida protected.

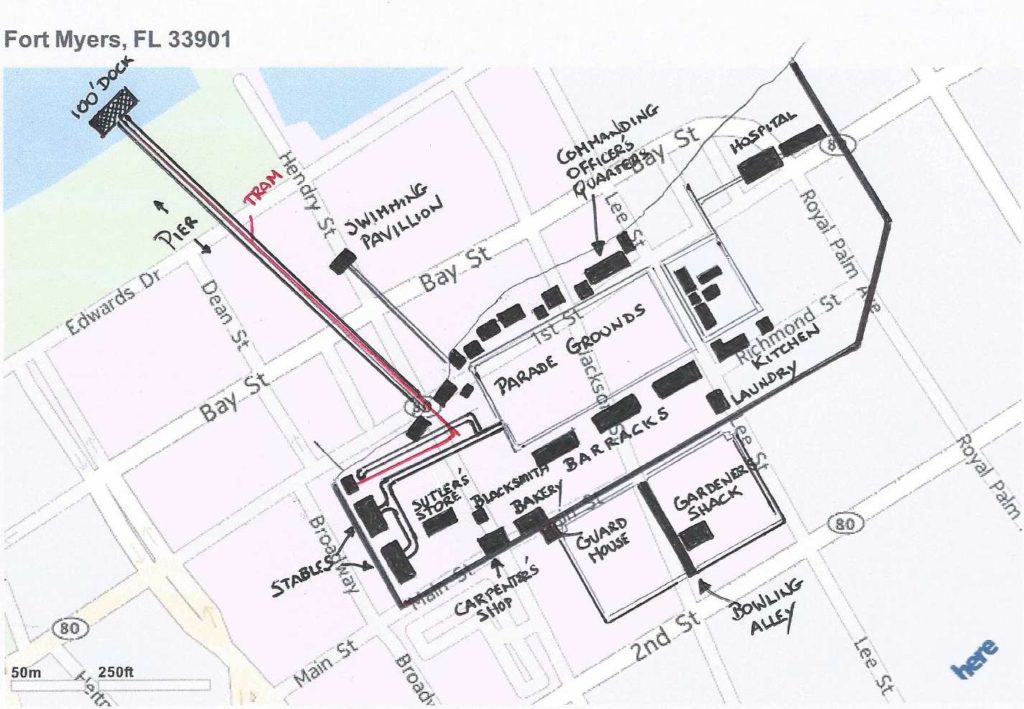

As the name suggests, Ft. Myers began its existence as a legitimate fort. It was built for use during the Seminole Indian Wars and abandoned in 1858. It caught the attention of the Union during the Civil War. Union troops were dispatched from Fort Zachary Taylor (Key West) in 1864 to re-garrison Fort Myers. When the troops arrived, they found a handful of Confederate soldiers attempting to burn the fort to the ground before it could be occupied. Timing was on the Union army’s side. The fort was re-garrisoned, expanded, and secured with a 7-foot earthen wall.

The Union troops garrisoned in Fort Myers were under orders to cause significant interruption in the shipments of cattle being transported to Confederate troops and also to thwart blockade runners who were trading between Cuba and the Florida cattle ranchers.

Five companies occupied the fort in the last 18 months of the Civil War. Amongst these was The 2nd United States Colored Infantry. (You heard that right!) An infantry of black men, fighting for the Union, were preventing Fort Myers from falling into Confederate hands in the middle of the Confederate state of Florida.

During the last 18 months of the war, Union Troops in Fort Myers confiscated 4,500 head of cattle. The cattle were then led down what is now McGregor Blvd, loaded onto Union ships, and diverted to Key West where they were used to feed the Union blockade protecting the Florida coast.

To further the insult, these Union troops were liberating the slaves they came across in their cattle raids. Fort Myers quickly became a refuge for escaped slaves, Union sympathizers, and those who were fleeing secessionists who were burning their homes and seizing their farms. Fort Myers would end up providing shelter to 400 of these such civilians by the end of the war.

As you can imagine, a Confederate military response was forthcoming. there was a military response building from the Confederates. In addition to the damage the troops in Fort Myers were effecting on the Confederate food supply, Florida residents as far up as Tampa loathed the black soldiers who taking their cattle and liberating their slaves.

In January of 1865 Major William Footman and three companies of Confederate soldiers (known as the “Cow Cavalry”) were dispatched to destroy Fort Myers. Major Footman began his 200-mile march with around 250 men. By the time he neared the fort, his militia had nearly doubled in size as angry farmers, fishermen and disaffected ranchers joined in as Major Footmans militia passed by.

They had planned for a surprise attack on Fort Myers. Most unfortunately, they happened upon a small group of Union soldiers on task outside the fort who were able to fire their weapons to warn of an attack.

His surprise attack now ruined, Major Footman sent a messenger to Fort Myers demanding its surrender. Captain James Doyle, of the 2nd United States Colored Infantry, responded “Your demand for an unconditional surrender has been received. I respectfully decline; I have force enough to maintain my position and will fight you to the last.”

The battle was fought in heavy, Florida rainfall and lasted but a single day. A reporter from the New York Times happened to be at Fort Myers when the battle, reported that “The colored soldiers were in the thickest of the fight. Their impetuosity could hardly be restrained; they seemed totally unconscious of the danger, or regardless of it, and their constant cry was to ‘get at them.'”

No soldier wants to be defeated, but the stakes were higher for the Colored Infantry. Being captured meant execution on the spot. The escaped slaves harbored in Fort Myers would to be returned to their owners, sold, or executed as well.

By nightfall, the Confederate troops came to the conclusion that they would not be able to breach the fort. They ceased fire, turned, and began their long march back to Fort Meade, leaving a wake of bandages, splints, and ration remnants.

In just six weeks, The Civil War would end with Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattax. The disruption in food supply to the Confederate troops was a factor in this.

The Battle of Ft. Myers would go on to be known as the southernmost battle of the Civil War.

Fort Myers went on to become a sizeable city. Twenty-two years after the Battle of Fort Myers, a group of men would cheer and slap each other on the backs as they renamed this land for General Lee.

The story of the Battle of Fort Myers and the role the 2nd United States Colored Infantry played in the Civil War was largely disregarded.

These American soldiers who held the fort, sheltered 400 civilians, and helped to weaken the Confederacy were not formally recognized by the City of Ft. Myers for 132 years. Even this late commemoration was not an act of goodwill. Instead, it was a community response to help reduce racial division after “Population Today” magazine accused Ft. Myers of being “the most segregated city in the South.” (Based on a University of Michigan study based on 1990 Census data.)

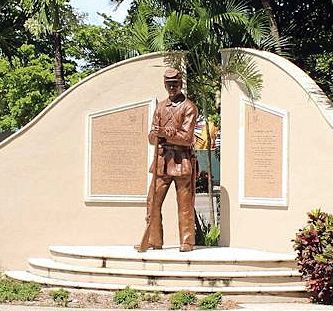

The City of Ft. Myers added a monument named Clayton to it’s Centennial Celebration. Clayton is dedicated to the 180,000 African Americans who fought for the Union during the Civil War. A plaque on the memorial honors The 2nd United States Colored Infantry.

Clayton is set quite a distance from where Fort Myers once stood. It is not the place of prominence in the city that General Lee has enjoyed for the past 54 years, but it will likely prove longer-lasting.

Clayton gazes upon the buildings of City government that have given so begrudgingly to the black community of Ft. Myers. Just beyond his gaze, past the lands of the old fort lies Dunbar, an area of Ft. Myers that has acted to compress the black community since the early 1900’s, to hold it immobile. Away from the rest. Out of sight. None of the blatant affluence of Ft. Myers exists here.

It is almost as if it was planned this way from the very beginning.

More on this in coming weeks.

Source: Clayton | ArtSWFL.com